A while ago, I was confronted with the stark reality of my life, and I knew I had to make some changes. It was my fault; I see that now. I had been sabotaging my future for months, with the deviousness of an arsonist out of Palm Springs.

It all started in February. I was under some fluorescent lights at the library, and I caught a glimpse of myself in the window. I looked like a Dutch boy, on the first day of school. I was so pale that my white button-up looked like a khaki shirt.

It began innocently enough. The next day I sat outside for a half-hour after I finished my lunch, basking in the late-winter California sun. I admit there was something seductive about the way my face got numb when I finally decided to go in. Sure, there were plenty of jokes in the workplace that first month, while I built up my melanocyte base. Years of indoor-living had left my skin cells deprived of melanin, a pigment that is produced by melanocytes. You can’t get any more melanocytes – yet – so the only way to get tan is to increase their production of melanin.

Nobody was joking in April, while I strutted around the office with the easy grin and glowing tan of an out-of-work actor. I admit, it was a little unnerving when a casting agent approached me and asked if I’d like to be in a movie about Australian convicts, but I was pulling it off well. When people joked about my tan, I jokes about it too, as if it were no big deal. By the end of the month, I had converted my wardrobe almost entirely to white Oxford button-ups, pastel ties, and white or off white suit jackets. With my chest darker by the day, I made sure to find an excuse to unbutton my shirt to my belly by four in the afternoon.

In May, I’d go without shaving for a few days to really get that Mediterranean look. But in order to really look like I was a Greek who had been milking the welfare state, I knew I’d have to decrease my latitude. Hawaii was the obvious destination, and I booked a flight. I made the classic mistake of a first-time visitor, and applied suntan lotion to my arms and face, before whisking off my t-shirt. Yeah, I spent some time in a burn unit; so what? When I got back home, I looked like I’d been squatting in front of a campfire for a month. The boss actually called me into his office and asked if, confidentially, there was anything about my liver health I might care to admit. To be mistaken for a sufferer of jaundice: in my mind, that was a compliment of the highest order.

People started taking their vacations, and there was no doubt I’d started a trend. I kept above the competition, though. Every weekend I’d fly to Cabo and lather myself with tanning products. I’d discovered a whole new world in “Banana Boat”, and the other bronzers, as I called them.

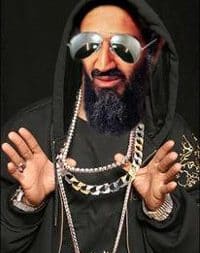

While I was spending weekends in Cabo, I got acquainted with a group of people like myself: white collar professionals, driven to ridiculous tanning by what we all knew, deep down, were feelings of personal inadequacy. It was a pitiful sight, the gang of us, our skin so dark, our clothes bleaches so white, we looked like a party of sailors shipwrecked in Western Sahara after a trek to the only oasis for miles. We tried to convince each other that tanning really didn’t matter to us. This from a guy who is so tan, you can see his skin through his shirt unless it is black or brown.

On the flight back, my mind was troubled. When I arrived at work the next day, I could tell that all the detergent I had used was unable to get the scent of Aloe Vera out of my clothes. I sat there, nervously, filing papers. I looked more ridiculous than John Kerry in October ’04, when, campaigning in Wisconsin he mysteriously acquired a tan so conspicuous it dominated campaign coverage for about a week. I knew I had to change. But I also knew that the habit was too hard to break on my own.

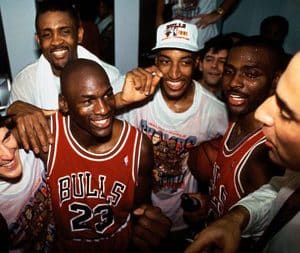

That is why I am up here in Trondheim. The days are already five hours long, and now that I’ve convinced the locals I’m no good at basketball, I can finally get some time in at the bar.